"The world breaks everyone, and afterward many are strong at the broken places." ~ Ernest Hemingway

My relationship with my dad has always been complicated.

One of my first comforting memories of him was when I was about six years old. I had strep throat, and my mom couldn’t leave work, so he took me to the doctor at Bethesda Naval Hospital — what’s now Walter Reed. I remember walking through the hospital, my small hand tucked inside his. I felt safe. After the appointment, he took me to the cafeteria for a hamburger. That may have been my favorite part.

I remember him coming home from work, often before my mom, sometimes starting dinner. He wasn’t a great cook, but he tried. There was a dish we called “hot dog surprise,” which usually involved whatever leftovers were in the fridge… plus hot dogs. And his infamous apple pie that looked beautiful, but the crust was so hard you needed a steak knife to get through it.

Stuckey’s and Sweet Corn

When I was young, there were long stretches when my dad wasn’t around. He was active duty in the Navy and would be deployed for months at a time. My mom, working full-time, somehow managed it all. When his deployments ended, she’d pack us into our wood-paneled Vista Cruiser and drive the four hours south to Norfolk, Virginia, to pick him up. We’d stop at Stuckey’s for pecan pie and buy sweet corn from roadside farm stands.

Those first days back were always a little tense. The smell of coffee and cigarettes, the creak of my dad’s ankles on the stairs: telltale signs that the house had changed, and that we kids couldn’t run wild like we did when he was gone. But there were also small pleasures. In the summer, I’d find him outside mowing the lawn. He’d come back in, sweaty and tired, and make one of my favorite meals: fried eggs over rice, the yolk runny, seasoned with salt and pepper.

And then there was his other side.

The Birthday Cake

“Happy Birthday!” he exclaimed one year, stepping into the house with the most spectacular cake I had ever seen. A gingerbread house stood proudly on top. He smelled of Old Spice, cigarettes, and something sharper — alcohol laced with celebration. I was thirteen. My mom was in the Philippines visiting family. I was so happy that for once, I was being celebrated.

Until I noticed the strange woman behind him.

Before I could fully register what was happening, they were already leaving. “Have fun — Happy Birthday!” he called out cheerfully, while she followed him, laughing nervously.

I stood there alone, staring at the cake. A heavy sadness washed over me as I realized he wasn’t coming back.

For years, that memory shaped how I saw him: a charming, erratic man whose love was unpredictable and whose presence was painful. He had a violent temper when he drank, and he drank a lot. I learned early how to stay small. I learned how to read the room for danger. And I carried those lessons into adulthood, choosing partners who mirrored that same volatility — fun-loving, charismatic, intoxicating, sometimes cruel.

But later, after I married and my husband joined the Air Force, my relationship with my dad began to shift.

Maps and a Road Trip

My parents helped me drive across the country to Monterey, California, where my husband was training at the Presidio’s language school. My dad meticulously planned the route, ordering AAA maps and marking all the stops. We drove for days — long stretches of endless highways, overnight stays at Best Western motels, through the Great Salt Flats of Utah, where the sky met the earth in a shimmering white haze; through Reno, where we played the slots, laughing like we had nothing to lose; through the desert Southwest, headlights cutting through the inky night. I remember dusty farm roads in rural California, stained fingers from eating sweet cherries we bought from a roadside stand.

We shared long, quiet hours, simple motel breakfasts, and road-trip conversations. Somewhere along the way, I learned more about my dad’s childhood — that he grew up dirt poor, that he didn’t own a proper pair of shoes until he joined the Navy during World War II. That he too had suffered abuse. It didn’t excuse anything, but it helped me understand the weight he carried.

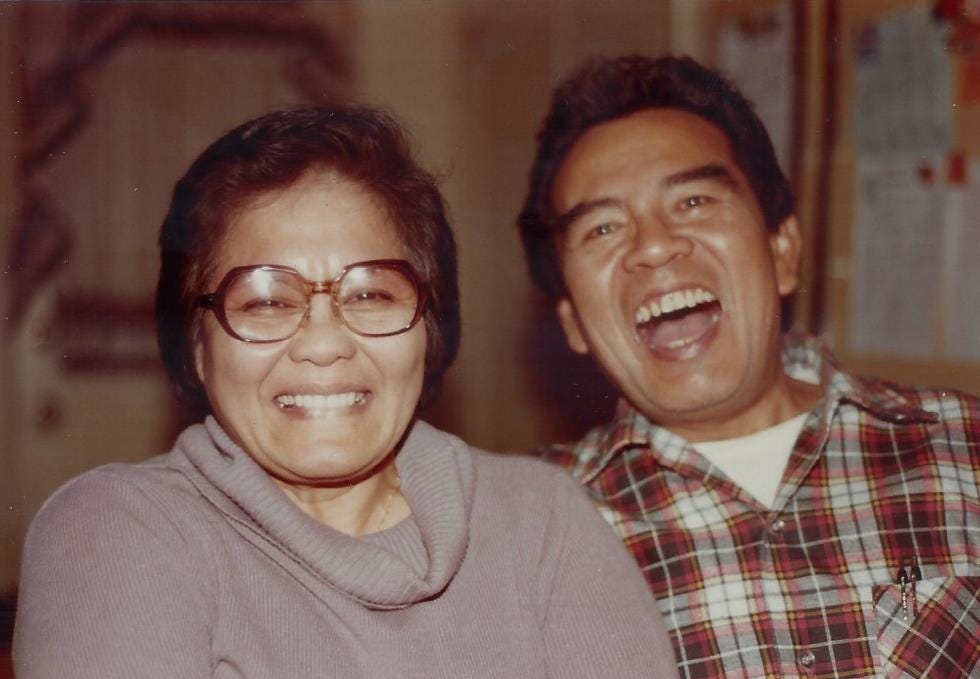

For the first time, I began to see my parents not just as the figures of my childhood, but as complex, flawed, human beings — trying their best, full of contradictions and capable of surprising humor, and tenderness.

The following year, before leaving to meet my husband in Korea, I worked a summer job at the same Army agency my dad had served since retiring from the Navy. Our offices were just down the hall from one another. Every morning, he drove us through rush hour traffic, both ways, navigating the stop-and-go with practiced patience. There was never any question that he’d take on that chore. He saw it as his duty, and there was something quietly chivalrous about it, as if he was making up for the times he hadn’t been there. While he drove, I sat beside him finishing my makeup. He knew I wasn’t a morning person and never rushed me.

My mom packed lunches for both of us, and my dad stored mine in his office refrigerator. At noon, he’d walk it down the hallway and deliver it to me with a simple, familiar nod. It was such a small gesture, but it landed deeply — an offering without fanfare. In those weeks, I saw him differently. I witnessed his competence, his quiet rituals, and the way his colleagues respected him. And I had a new respect for him too, not with blind forgiveness, but with the clarity that comes from seeing someone more fully.

Those moments didn’t erase the pain of my childhood. They didn’t undo the fear, the confusion, or the longing. But they softened the edges. They let more truth in.

Making Room for the Whole Story

My father was never just one thing. He was a man of contradictions: tender and terrifying, loving and unreliable. And through the lens of time, I’ve learned to hold all of it.

Six months after he finally retired from the Army — after more than thirty years in the Navy and nearly two decades of Army civil service — my dad had a stroke. He had plans for retirement: to travel with my mom, to learn how to play golf, to enjoy the life he had worked so long and hard for. Those fifteen years leading up to his stroke were probably the happiest my parents were as a married couple. He had mellowed, and their life had grown more peaceful. When his health declined, my mom retired early to care for him, and she remained his caregiver for the next fourteen years until he passed in 2008. That chapter with its quiet grief and my mom’s daily sacrifices is a story I have yet to fully tell.

Father’s Day can be complicated. For some of us, it’s not a Hallmark holiday. It’s a day that stirs grief, gratitude, and memory in equal measure. But today, I’m honoring the whole picture. The man who made hard-crusted pies and runny-yolk eggs. The man who drove me cross-country and delivered my lunch down the hall. The man who hurt me, and who, in his own imperfect way, also loved me.

And maybe that’s what healing really asks of us: Not to forget the harm, but to make room for the whole story.

To tolerate ambivalence.

To live with the ache and the grace.

The wholeness of a life, imperfect and real.

Additional Resources:

🌿 The Reclaim Series: Summer Wellness Retreats

Join us for The Reclaim Series—and if you’ve been thinking about it, maybe this is the sign you’ve been waiting for. Flash sale for Embrace & Evolve ends tonight at midnight. A weekend of rest, connection, and meaningful change at the beautiful Goodstone Inn. Explore the details here.I’m excited to be offering a recurring 8-Week Mindfulness for Stress Management series through The Mindfulness Center! Learn evidence-based practices to reduce stress, build resilience, and reconnect with a sense of calm and clarity. Perfect for beginners and seasoned practitioners alike. Learn more and register here.

For a deeper dive, consider one-on-one sessions. Founding Members get exclusive discounts on sessions. Check out my offerings here.

Invite your friends and earn rewards

If you enjoy Mindful Reinvention, share it with your friends and earn rewards when they subscribe.

I understand the trauma of growing up in an alcoholic family. It’s painful. The hallmark of it is the unpredictability of my life 24/7. The nascent anger floating in the air was always lurking there. I think the reason I got married when I was nineteen was because I needed to get out of my parents’ house by whatever means necessary. I married someone who was extremely unsuitable and that left a pretty bad scar. Sometimes subtle things like this can cause a life event that haunts me to this day.

I was able to use the lessons I learned from the alcoholic home in helping me cope and be realistic about what to expect in life.

The time I had a good relationship with my dad was when I worked for him as a dental assistant. My dad loved his profession and was a perfectionist in his performance. He took enormous pride that a kid from upstate New York was a dentist who worked with well-known patients. Dad was a born teacher and I was able to understand a great deal about dentistry. He was always happy at work so that brought out his best side. That happened from my age of 15 in 1957 until he died in 1969.

The most difficult time with him is when he would begin ranting and yelling about anything that struck his fancy at the moment. He would do things that really upset my mom like saying mean things about her relatives. He could be a most charming person when you met him or a total wretch. To this day I abhor living in a chaotic world. No wretches allowed!

Amen my friend. What an honest depiction of your dad. We are all so multi-faceted, complex and incredibly blessed to be on this earth for such a short time.